In This Article:

Christian Quintin doesn’t paint what he sees. He paints what you remember feeling—before you had words for it. His images arrive like déjà vu: a tree that’s also a dancer, a face made of rooms, a landscape that breathes.

Born in coastal Brittany and now working in Northern California, Quintin has developed a body of work that defies easy classification. It’s romantic, surreal, meticulously crafted, and deeply philosophical. He offers no slogans, no manifestos—only an invitation: “See the art as one would read poetry, hopeful that one would wander into its imagery.”

For more than four decades, he has followed this invitation himself, using ink, oil, graphite, and pastel to explore the twin landscapes of the psyche and the natural world. What emerges is not a split practice but a unified vision: a visual philosophy that connects inner consciousness and outer terrain in a seamless, symbolic language.

Quintin’s art begins with a coastline. He was born in 1957 in Saint Brieuc, a port town on the moody northern coast of Brittany. There, amid ruined castles and storm-lashed cliffs, he developed an early sensitivity to nature’s grandeur and melancholy. One island in particular—L’Île de la Comtesse—became a mythic point of return in his later works. Its architecture, its solitude, its storybook aura still appear like recurring dreams.

In 1975, he moved inland to the ateliers of Paris, where he studied at the prestigious Beaux Arts Academy. Here, his romantic instincts were tempered by classical discipline. The precise draftsmanship, control of form, and mastery of materials that would define his later work were forged during this period. He absorbed the legacy of French Surrealism, but also the Symbolists and the Romantic painters. Not to shock, but to reveal.

Then came the turning point: in 1981, Quintin crossed the Atlantic and settled in Northern California. In the vineyards and valleys of Sonoma County, he found not only beauty but resonance. “I feel the same spirit in a tree as in myself,” he’s said. And so the California landscape became his second vocabulary—his trees, skies, and rivers not just depicted, but communed with. The old myths of Brittany had found their mirror in the sacred ecology of the American West.

Quintin’s surrealist works are not dreams in the Freudian sense, but interior constellations—maps of memory, emotion, and presence. Often rendered in pen and ink or oil, these compositions contain layered imagery, uncanny metaphors, and astonishing technical precision.

In his self-described “kaleidoscopic consciousness” paintings, boundaries dissolve. In The Aviary, Quintin’s face emerges from within a crystal, his neck becomes the trunk of a tree, and his hair unfurls as leafy canopy. It took him six months to complete—and the result is less a portrait than an ecosystem of self.

Works like La Porte Ouverte, inspired by a Rumi poem, are visual meditations. “Why stay in prison when the door is wide open?” asks the poet. Quintin replies not with words, but with seven months of crosshatched mystery—symbols and figures that blur the edges of logic and dream.

This is not automatism. These images are not accidents. They are built, slowly, with intent. “When you draw a tree, you also draw yourself,” he’s said. Each stroke is a negotiation between spirit and form, between idea and the hand.

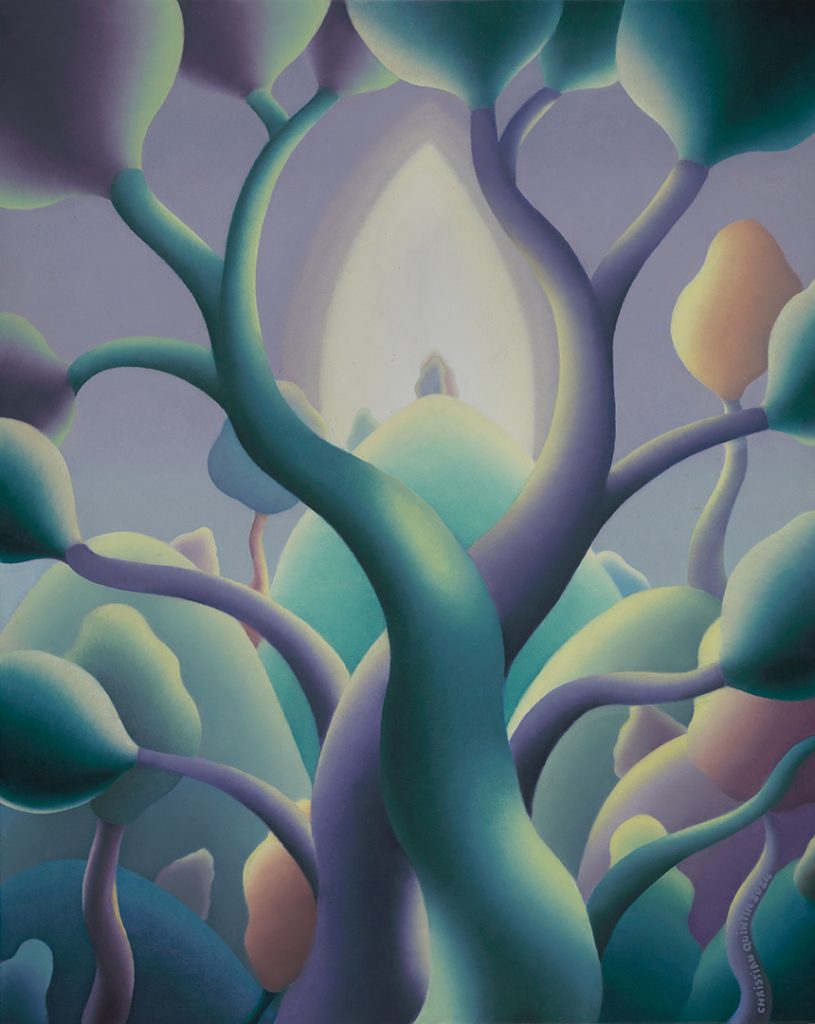

Alongside his surrealist works, Quintin creates luminous landscapes—emotive sceneries in oil or pastel that seem to hum with life. These aren’t documentations of place. They are emotional terrains.

Trees in his paintings sway like dancers (Leaves of Absence) or embrace like lovers (Les Amants). A river doesn’t just reflect the sky—it carries memory, mood, and metaphor. In A Lake Color of Emeralds, he writes, “The sky is brown-orange with violet, the lake bright emerald, the sea olive green.” Color is feeling. Shape is story.

California’s hills and Brittany’s coastlines repeat as characters in his visual vocabulary. But even in his most “realistic” landscapes, there’s always a pulse of surrealism. In West Sonoma County, a floating face emerges from clouds, its lips becoming an island. In Putah Creek, An Eruption of Life, nature bursts into exuberance, as if consciousness itself were blooming from the soil.

This is not a dual practice. His landscape and surrealist modes are not opposing forces. They are mirrors. Each feeds the other. The symbolic enters the natural; the natural becomes symbolic. It’s all one vision, seen through two eyes.

Quintin’s philosophy is simple and radical: art should be beautiful, emotional, and intuitive. It should not tell you what to think—it should give you space to feel.

“I do not have a message,” he’s said. “But I feel compelled to convey the feelings that flow through me as I attempt to create something beautiful.”

In his writings, he advises artists to draw the first thing that comes to mind, without judgment. “Intuition first. Technique follows.” He matches each work with the medium it calls for—pastel, oil, graphite—like a musician choosing an instrument. Each line, each hue, is tuned.

This rejection of irony, of didacticism, sets him apart. In an art world often preoccupied with critique, Quintin returns us to wonder. He creates not to argue, but to remind.

For years, Christian Quintin worked steadily in Northern California, exhibiting at respected regional galleries and creating public commissions across the state—from hospital lobbies to city murals. His technical mastery and poetic voice earned him accolades: the Grumbacher Award in 1987, an Award of Excellence from the California State Fair in 1990.

But a key turning point came in 1999, when the Vorpal Gallery—which famously introduced M.C. Escher to American audiences—began showing his work. This association placed him in a lineage of artists who combine meticulous technique with mind-bending ideas.

In the 2020s, a new chapter began. With representation by Lorin Gallery, Quintin’s work entered the international stage: KIAF in Seoul, Art Central in Hong Kong, shows in Paris, Los Angeles, and soon, the Morrison Gallery in Connecticut.

He didn’t change his work to fit the art world. The art world caught up.

Over the years, critics have returned to the same words: beauty, mystery, technical mastery. Alhia Warren called his work a “beautiful intimate mystery.” Suzanne Munich titled her review “Mental Landscapes.” Dan Taylor wrote in the Press Democrat: “Emerging Beauty.”

A 2022 Calabi Gallery review stood out: “In an era largely devoid of it, his work is beautiful. We could all use more beauty in our lives.” That wasn’t flattery—it was diagnosis. Quintin’s work fills a gap left by cynicism and irony.

Christian Quintin belongs to the surrealist tradition—but not only. His closest kin are those who make the impossible legible: Dalí, Magritte, Escher. But unlike many surrealists, Quintin doesn’t aim to unsettle. He aims to awaken.

In that, he shares something with the Visionary Art movement of Northern California—the psychedelic spiritualists of the 1960s and their heirs. But where their work often explodes with color and chaos, Quintin’s vision is slower, quieter, more classical. His is a sacred geometry of thought and feeling.

He is, in the best sense, a bridge. Between Europe and America. Between precision and emotion. Between the tree and the dream.

Quintin is currently represented by Lorin Gallery in Los Angeles and Paris, with upcoming shows at Morrison Gallery in Kent, Connecticut. His past exhibitions include solo and group shows across California, Paris, Seoul, and New York.

If you encounter his work in person, take your time. Let your eyes wander. Look twice. Look through.

Notice the metaphors buried in the bark. The layers behind the face. The color that feels like music.

Christian Quintin’s art is not a detour from reality. It is a reentry into its hidden dimension—the one you feel when you stand beneath a storm-colored sky, or close your eyes and remember the smell of the sea.

In a culture of speed and spectacle, he reminds us of slowness, of intricacy, of care. His work is not loud, but it echoes. It does not preach, but it moves.

He shows us that beauty is not escape—it is a form of resistance. And art, when made with attention and soul, becomes what one curator called it: a “wondrous sanctuary for the soul.”